When Christmas Comes to Vienna

When Christmas is coming, all people, all regions, even all families have their own traditions to celebrate this festive time.

aus: "Wenn's in Wien weihnachtet", Christine Schäffer, Edition Mokka, ISBN 978-3-902693-63-1

A special position regarding such traditions is held by Vienna. Vienna is not only the heart and center of Austria, but also of a former global power: the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Here, in the capital of both the democracy and the former monarchy, traditions took their origins and travelled over the whole country.

In this book we want to find answers to questions such as how Christmas was celebrated in the times of the monarchy, or how the imperial family celebrated it. Did Empress Sisi, dressed in exquisite gowns, admire a Christmas tree with her children, delighted by their excitement? Who had the first Christmas tree in Vienna? How did the citizens celebrate Christmas? And what about Christmas in the 21st century? Which traditions do we still follow today – what is new? If you have grown curious, you can find the answers below.

Christmas Traditions in Vienna through the Ages

The time before Christmas is full of preparations and excitement. The days and nights leading to Christmas Eve have always been filed with festivities. In the Middle Ages already citywide events took place for citizens, travelers and the aristocracy. These festivities were both secular and religious, just like today. The wintery happenings of old times are enthralling for modern people and can transport them to dreams filled with fantasy.

-

The Scarlet Race

One of these traditions in winter was the scarlet race. It took place until the mid-1500s and was a horse race. It started in St. Marx, led to the Wienfluss and ended again in St. Marx. One evening prior to the race, trumpets would announce it at the Hohe Markt, a gathering point for the people as well as a market place. The winner of this race would receive a piece of scarlet. Scarlet was a highly valuable red wool, which was worth more than a crossbow or a pig! These two things namely were the second and third prices respectively. Altogether, six to thirteen riders participated in this race – this relatively small number is probably due to the price for a racing horse itself and the entry fee for the race. It was one Hungarian forint, which was one of the strongest currencies in those days!

-

Oracle Traditions – Who Will Be My Love?

There is a surprisingly great amount of old traditions that want to predict luck or a wedding. Especially the Andreasnacht, the night of St.Andrew’s on November 30, was said to be ideal for predictions. There was for example the oracle of throwing shoes: One would throw a shoe over their shoulder and, depending how it fell down, one would know if they would marry or not. If the tip of the shoe pointed to the door, one stayed single – if the heel pointed to the door, a marriage was bound to take place.

A similar oracle is that of the walnut shells which was very popular. Two candles were stuck on two walnut shells each, lit and put into a bowl of water. The shells represented oneself and the person one was in love with – if they bumped into one another, you were destined to come together with your sweetheart.

Tired out from all these oracles, you should eat a baked figure made out of water, flour and salt and then go to bed. It was said that this figure would bring dreams of your future husband – but only if you ate it in the night of Saint Andrew’s.

It gets a little hotter when it comes to lead melting. This is a very popular tradition in Austria even though it is now mainly done on New Year’s Eve, to find out what the new year will bring. A few centuries ago though, people did it on Christmas Eve. And it worked – just like today – like this: You melt lead over a little fire, let it drop abruptly into cold water and let it cool. Then you start guessing. What kind of form does the lead have now? Back then people said a woman could see the tool of trade of her future husband in it!

Melting lead used to be a much slower process than today. Impatience grew easily when people waited for the lead to melt over a little candle light – the melting point of the lead was too high and therefore it took a very long time to become liquid. Only the Austrian Erwin Perzy I. had a wonderful idea how to melt the lead more quickly. And this is what happened: On New Year’s Eve in 1900 he saw how long it took to melt the lead. The lead was, by the way, won from lead bullets. Little shreds of lead were pulled from venison before it was cooked and held on to for New Year’s Eve! So there Perzy I. was, watching his sisters slowly melt lead and he started to think how he could lower the melting point of it. He knew a lot about metals so he added tin to the lead – it had a much lower melting point and therefore the whole process could be accelerated. His sisters were thrilled. The next thing he did was to create a mould in the form a caulkin. A caulkin is a stud for a horse shoe, screwed into the metal to protect the horse from slipping on muddy grounds. They sometimes came loose and when a person found a caulkin on the streets it was a sign of good luck. So Perzy I. created little caulkins made from his tin-lead alloy and gifted them to friends and family in the next year. They were as excited about it as Perzy’s sisters had been and he started to produce his lucky charms on a larger scale. This production still continues to this day through his grandson Erwin Perzy III. in the form of the world-renowned Wiener Silvesterguss!

It is not surprising that mainly women participated in the aforementioned oracle traditions and that they were mostly concerned with marriage. Most women needed a husband in order to survive – a marriage usually promised a better life for the woman than remaining single and alone, with limited prospects of finding adequately paid work.

Therefore we shall continue with another traditional oracle day, December 21st. When a girl wished to know whom she would marry, she should kick against her bed three times before going to sleep and say the following:

Bedpost I kick you,

St. Thomas i beg you,

Let me see,

The dearest of me.

If she followed these instructions, she was sure to see her future husband in her dreams.

A more general kind of luck is predicted with the last oracle which still exists in Austria to this day: On December 4, some twigs were cut off a fruit tree – ideally of a cherry tree. These twigs are called Barbara’s twigs, as they are cut on St. Barbara’s day. They are watered at home and if they blossom before Christmas, the New Year will be a lucky one!

All these notable nights, St. Andrew’s and St. Thomas’ night as well as Christmas Eve, were called “Lösselnächte” or “Losnächte” in Vienna, which roughly translates to nights of lots. According to popular belief these nights were especially potent for oracles.

Today only the tradition of lead melting and cutting Barbara’s twigs are still practiced. Traditions falling out of fashion are completely normal and even good – they leave room for new traditions of new generations after all. We Viennese people of the 21st century have our own customs that are important to us and remind us of our childhood. We fondly remember the whole family attending a Christmas market and drinking punch together or lighting the candles of the advent wreath every Sunday in December, telling stories and singing songs in its soft light. And especially distracting the children on Christmas Eve, for example with a walk or a visit to the theater, so the Christkind has enough time to put presents under the Christmas tree.

-

Riding a Sleigh

The customs and traditions described above took place indoors, but naturally people didn’t stay in their homes all winter long. They went for long walks in the park, went ice skating or rode a sleigh.

Only rich and noble families could afford a proper sleigh ride. Their ways often led them to the Neuen Markt, where they rode over the square in sinuous lines. The squares were blocked for commoners then, so they would not come in the sleighs ways.

The sleighs also turned towards castle Schönbrunn often – the imperial family enjoyed inviting other aristocrats to share the beautiful sights of their gardens and frozen ponds with them.

If there was too little snow, the nobility had to use regular carriages which evoked their dissatisfaction and was a matter of complaint in some years.

The middle class had to content themselves with alley rides. They did not have beautiful sleighs but carts similar to those used in trotting races. The Viennese of course also had to avoid crowded places and used unbuilt areas for their joyful rides.

If one were to look for such sleigh rides today they would not find any in Vienna’s busy streets –much to the delight of motorists, the roads are kept clear of snow. But of course there is always the possibility of riding a characteristic Viennese Fiaker, even in winter! They provide thick blankets for their passengers as well as the horses and the ride leads past Stephansplatz, Heldenplatz and Michaelerplatz where knowledgeable drivers tell stories about Vienna and its architecture.

And one must not forget sledding! Outfitted with a wooden sled, the parks of Vienna or the meadows of the “Viennese mountains”, for example Kahlenberg, become proper pistes for young and old.

Traditions Are Ever Changing

Christmas was not always celebrated the way we do it today. Back then, there was no tree and no nativity scene. Advent calendar? That too is a relatively new invention! And as is common with new inventions, at first it is observed with great scepticism. This scepticism is amusing for modern minds, which is why a direct quote recording is played back. After reading, each individual can decide which form of celebration is the nicest ...

-

Nikolaus and Christkind

In Austria and therefore also Vienna, it is the Christkind, often portrayed today as an angel, that delivers everyone’s presents on Christmas Eve. But that wasn’t always the case! 300 years ago Catholic families were visited by St. Nikolaus on the 6th December, who was the one to bring small presents.

The celebration of St. Nikolaus was the most important festivity in Catholic Christmas time. Catholic families wanted to distinguish themselves from Protestant families, who did not celebrate St. Nikolaus but the Christkind on December 24th. Back then, Catholic and Protestant traditions diverged strongly from one another. This changed in 1781 when Emperor Joseph II. signed the Patent of Toleration.

From then on, Protestant traditions were adopted by Catholics. For example, the Christkind started to deliver the presents and the main focus of celebration shifted from 6th to 24th December. Today, Catholic families look forward to both Nikolaus and Christkind, but the latter is more prominently featured.

Speaking of the Christkind, it is not, as some may assume, little baby Jesus but the personification of the Holy Ghost!

-

Christmas Even by Thusnelda Wolff-Kettner

Dawn spins its web through the alleys,

As the sleigh bells merrily ring.

The Christ child quietly enters

Through the snowed covered doorsteps.

In front of closed doors listening

Breathlessly filled with wonder.

Merry children whisper,

When inside secrets rustle.

Today everything has a deeper meaning.

And when the bells gently rings

It sounds like religious angels singing

That is heard through all the old alleys -

Christmas Tree

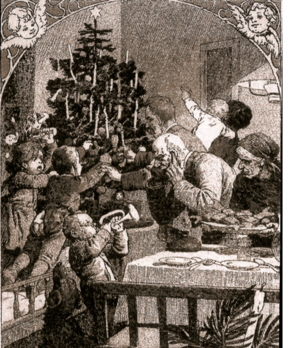

The Christmas tree, as it is known in Austria today, has also developed from Protestant traditions. Could we glimpse into prosperous Protestant households 300 years ago, we would see a little Christmas tree. In Catholic households however we would see a nativity scene. They did not have a Christmas tree – only a tree from St. Nikolaus who delivered it on December 6 together with the children’s presents. It was first decorated with apples, later with fruits and nuts and eventually with glass baubles and sweets. But why was it decorated in the first place? The festive fir tree actually symbolizes the apple tree of the story of the fall of mankind. Aside from Christ’s birth on December 24th, Christians also commemorate Adam and Eve’s fall and that they, with all humanity, are absolved from their sins.

Especially the imperial family has to be thanked for the successful dissipation of the Christmas tree in all Viennese homes, regardless of religious background. Henriette von Nassau-Weilburg, the wife of Archduke Carl, was the first member of the imperial family to prepare a beautiful Christmas tree – this was in 1816.

As soon as it was made known that even the Emperor’s family participated in this custom, most wealthy families acquired trees for their own homes.

But Heinrich Anschütz was also a strong force in popularizing the Christmas tree among Vienna’s people. Anschütz, a well-known actor of the Burgtheater in the 19th century, arrived in Vienna in 1821. He wished to celebrate Christmas as he knew it from his Protestant home back in Germany and went on a search for the ideal fir tree. In his recount it is very easy to see how much Vienna has changed in the last centuries. Next to a nativity set we can now find a glowing Christmas tree.

The Christmas tree also met with some resistance at first – it was, after all, a Protestant custom and not a Catholic one. Archduke Johann, who experienced the debut of the Christmas tree first hand, wrote in his diary how little he appreciated the hot light of the candles and the absence of the crib.

But these sentiments were held by a minority of people and the Christmas tree grew on every Viennese citizen, becoming a well-loved part of Christmas Eve.

In order for people to be able to buy trees enough specimen had to be brought to Vienna of course – soon, there were fir tree vendors on every street corner and a Christmas tree market was established.

Frances Trollope, an English novelist, witnessed Vienna before Christmas and relates how the city turned into a veritable forest. She describes the joy of those who moved past the numerous trees and how their happiness was equal to that of a rich lady, choosing expensive gifts for her friends and family.

The Christmas tree therefore has not only brought changes to our homes but also to the Viennese streets themselves: next to a lovingly made nativity set is a beautifully decorated tree. Often there are two sets, one made of wood and another out of paper, which has been crafted by the children of the family in primary school. These paper nativity sets are proudly presented at home and placed next to the wooden set.

-

Nativity Sets

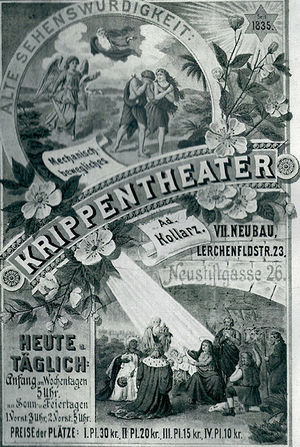

The custom of installing a nativity set stems from the Middle Ages. A nativity set was supposed to be a realistic depiction of the miraculous birth of Jesus. As there were no Christmas trees yet on which Catholics could vent their creative energy, they created more and more opulent nativity sets instead. Public sets started to incorporate complicated mechanisms to surprise and entertain the audience. In 1716, a Viennese newspaper reported on an installation of the Nativity that not only included a little pond with fishes but also trick fountains and angels that descended from the heavens. Even the secrets of Christ’s childhood were portrayed using shadow play. Obviously, the creators of this nativity set did their best to entertain the public. One might assume that this set was located in the middle of a market or some other secular space – but this is wrong: it was just next to the parish church of St. Anna!The clergy apparently chose to entertain their flock in order to both convey the Christian doctrine as well as draw their “audience” into the chapel.

With time, this secular spectacle of course began to separate from its clerical beginnings, especially when Maria Theresia, in 1762, prohibited the installation of nativity sets in churches. This prohibition strengthened the trend of erecting sets in a family’s own home and to decorate them more and more ornately. These nativity sets soon reached lengths of impressive two metres! To find the ideal set for one’s home, the nativity set market at the Graben was the right address to stop by at. During the 19th century however this market was substituted for a Christmas tree market.

But this does not mean that there are no nativity sets in Vienna’s homes anymore, far from it! Here and in all of Austria the most beautiful sets one can dream of are found – and crafted. Lovingly, they are created from scratch with moss, wood, plaster and wire. One of the most famous nativity set builders of all times came from Austria and his artworks were and are coveted all over the world, from Germany to Canada. Alexander Schläffer was the name of this talented man, who made his sets with a lot of love and patience and who collected the twigs for them himself, in Salzburg Pinzgau. Schläffer even built a nativity set as the representative show piece of Austria for the Summer Olympics in Mexico City in 1968.

But even the most beautiful private sets could hardly compete with the elaborate mechanics of public nativity sets in the 19th century, called Krippenspiele. They were no mere static nativity sets but used moving parts and special effects. They did not only display the Nativity but entire sequences of the bible, starting with the Genesis! These nativity plays truly were little theatre plays and of course an entrance fee had to be paid by the audience.

Especially the Altlerchenfelder Krippenspiel was a great spectacle. It was one of the last large nativity plays in Vienna, at the turn of the last century. Effects were used in abundance: The burning bush truly caught fire; when the Noachian Flood began the audience was sprayed wet from rain and Manna came from the heavens.

Today, there is a particularly crazy Krippenspiel in the time before Christmas in Vienna. It takes place in the Kabinetttheater in Porzellangasse 49: It is Dadaist and written by Hugo Ball himself, a great Dadaist. In seven images the Nativity story is told, accompanied by Dadaistic poems, sounds and different voices. During the show baked apples are prepared, their smell tickling the audience’s noses, which can be eaten after the play.

-

The Advent Wreath

The Advent wreath symbolizes the passage of the four weeks of Advent, a time of expectant waiting and preparation for the celebration of the Nativity of Jesus. It was most likely first made by the Protestant pastor Johann Hinrich Wichern, who managed an institution for poor children in Hamburg, Germany. The children simply could not await the celebration of Christmas anymore and asked for something that would show them how much longer they had to practice their patience. Wichern had a fantastic idea: he installed a wreath with 24 candles on a wheel. Twenty of them were small and white. The other four, which were lit ever Sunday in Advent, were large and red. This first happened in 1839. Children and adults alike were thrilled by this and the custom quickly spread in Germany. In Austria and Vienna the wreath only became a tradition after the First World War.

The Advent wreath is not only a symbol of light itself, its individual parts are also symbolic for closeness to God, love and hope: The circle of the wreath for example stands for eternal life, for resurrection. The green twigs from which the wreath is made symbolize the hope of Jesus’ return and the red colour of the candles is God’s love for us. Violet candles on the other hand are an invitation to reconsider one’s life and choices.

In some advent wreaths a rose or white coloured candle takes the third spot (never the fourth!). It is lit on Gaudete Sunday, which translates to “Rejoice” Sunday. It symbolizes the anticipation of Christ and is lit on the third Sunday.

Sometimes a wreath has each a violet, red, rose and white candle which are also lit in this order – the white one being the traditional festal colour of the Western Church.

Gaudete, gaudete!

Christus est natus ex Maria virgine, gaudete!

Tempus adest gratiae

Hoc quod optabamus,

Carmina laetitiae

Devote reddamus.

Deus homo factus est

Natura mirante,

Mundus renovates est

A Christo regnante.

Ezechielis porta

Clausa pertransitur,

Unde lux est orta

Salus inventi

Ergo nostra contio

Psallat iam in lustro;

Benedicat Domino:

Salus Regi nostro.Rejoice, rejoice! Christ is born of the Virgin Mary, rejoice!

The time of grace has come – what we have wished for, songs of joy

Let us give back faithfully.

God has become man, (with) nature marveling,

The world has been renewed by Christ (who is) reigning.

The closed gate of Ezekiel is passed through, whence the light is raised, salvation is found.

Therefore let our gathering now sing in brightness

Let it give praise to the Lord: Greeting to our King. -

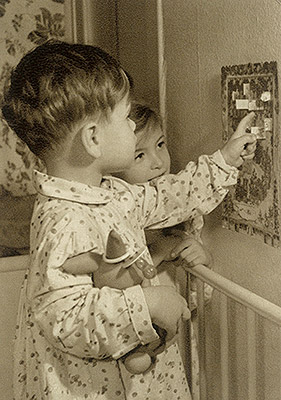

The Advent Calendar

The Advent calendar is supposed to make the waiting for Christmas more endurable. A small daily ritual eases the overall excitement and turns the expectant gaze from a distant Christmas Eve to the much closer following morning. Around 1800 for example it was common that children in convent schools were allowed to put some straw or cotton in the crib of baby Jesus every day in Advent. Later on tear-off calendars were introduced or calendars where a simple chalk dash was added every day.

Gerhard Lang’s mother had a particularly nice idea at the end of the 19th century. She gave her son 24 pastries, allowing him to eat one every day until Christmas had arrived. Gerhard Lang became a successful publisher as an adult and created his own advent calendar in approximately 1904: he printed 24 little images that could be cut out and glued on an additional cardboard with little verses on it.

Nowadays Advent calendars are a must-have for everyone and they range from simple calendars with images to calendars filled with chocolate or even precious eau de toilet. At school children tell each other excitedly what they found in their calendars that morning and sometimes bring their gifts along. In some classes teachers even make their own calendars and fill them with little somethings for their pupils.

-

Knecht Ruprecht

Theodor Storm

From out the forest I now appear,

To proclaim that Christmastide is here!

For at the top of every tree

are golden lights for all to see;

and there from Heaven’s gate on high

I saw our Christ-child in the sky.And in among the darkened trees,

a loud voice it was that called to me:

‘Knecht Ruprecht, old fellow,’ it cried,

‘hurry now, make haste, don’t hide!

All the candles have now been lit --

Heaven’s gate has opened wide!Both young and old should now have rest

away from cares and daily stress;

and when tomorrow to earth I fly

“it’s Christmas again!” will be the cry.’And then I said: ‘O Lord so dear.

My journey’s end is now quite near;

but to this town I’ve still to go,

Where the children are good, I know.’‘But have you then that great sack?’

‘I have,’ I said, ‘it’s on my back.

For apples, almonds, fruit and nuts

For God-fearing children are a must.’‘And is that cane there by your side?’

‘The cane’s there too,’ I did reply;

but only for those, those naughty ones,

who have it applied to their backsides.’

The Christ-child spoke: ‘Then that’s all right!

My loyal servant, go with God this night!’From out the forest I now appear;

To proclaim that Christmastide is here!

Now speak, what is there here to be had?Are there good children, are there bad?

English (Englisch von © 2006 Denis Jackson. Isle of Wight. http://www.theodorstorm.co.uk/Life/knechtRuprecht.htm)

-

The country saying

If the winter stays away in December, there is usually a late winter.

December warmth is followed by ice.

White fog in the winter is caused by frost.

If there is no winter until the Epiphany, then there will be no winter at all.

Traditional Meals in Advent

Not all animals could be brought through the winter and meat could only be conserved in the cooler season, which is why most livestock were butchered towards the end of the year. In November, poultry is still butchered today according to old traditions – the so called Martinsgansl, the goose eaten for St. Martin’s Day on November 11, comes to mind. After the poultry, with cold creeping in more and more, the fish lakes are emptied and the crabs processed. The last harvests of autumn fruits, among them chestnuts, pumpkins, pears and appels, are brought in and dried to last. The store room was of course also filled with eggs and honey.

The big finale was marked with butchering the Christmas pig and making delicacies such as sausages, ribs or hams out of it. Gathering all these delectable foods together, from fruits to roast meat, it is obvious that winter and Christmas time have always been a culinary zenith of the year. One could eat to their heart’s delight! Except for December 24 which is considered a day of fasting and meat should definitely be avoided. But let’s not forget – firstly, the bigger part of society did not adhere to this too strictly and secondly, fish was not considered meat – so it could be eaten without guilt or bad conscience. Because of the latter, fish was and is a traditional Christmas dish. A common menu for a middle class family in the early 1800s was a fish soup to start, followed by cod with potatoes and lamb’s lettuce.

-

Fish soup

Ingredients

700 g fish (with head and roe)

Butter

Parsley root

1 onion

½ celeriac

½ nutmeg freshly grated

Salt

Pepper

Ginger

2 tbsp flour

Bread rollsPreparation

Soften the butter in a pan and fry the innards of the fish. Add the rinsed and cut vegetables and fry together. Add water, boil and add seasoning to the soup. Serve with bread rolls.

-

Carp cooked in beer

Ingredients

1 kg carp

Salt

Onions, cloves, nutmeg

BeerPreparation

The original wording of the old recipe: “The carp is scaled, gutted, torn and cut into pieces, first a little salt is sprinkled on to it and then wiped off and put into a casserole or pot with lots of chopped onions and a few cloves and mace blades. Pour beer over it until it is completely covered and cook it over a strong fire until there is nothing left of the beer but a smooth stock and then it is served."

-

Christmas goose

Ingredients (for 4 people)

1 ready-to-cook goose, approx. 3 kg

3 apples

200 ml red wine

100 g white bread

2 onions

Mugwort

Salt, sugar and lemon juice

ParsleyPreparation

Wash and thoroughly dry the goose. Wash the apples and remove the core so that a small base remains standing. Pour a little wine into the apple openings and fill them with pieces of white bread.

Salt the inside and outside of the goose, fill it with the apples, the quartered onions and mugwort and finally sew it closed. Tie the joints and wings to the rump.

Fill a roasting tin with hot water reaching 1 cm, add salt, place the goose into the tray with the back facing down and slide the roasting tin on to the lower rail of a 200°C preheated oven. While roasting, poke the goose below the wings and joints so that the fat can be released.

As soon as the juices start to turn brown, add more hot water to the roasting tin in order to replace the evaporated water. Now reduce the temperature to approx. 150°C. Baste the goose with the juices every now and then so that it is brown on all sides.

If the goose is cooked (calculate approximately 1 hour cooking time per kilo of meat), loosen the string and take out the filling.

Force the filling through a sieve. Mix the cooked juices and the sieved filling with a little water on a hob and turn it into a sauce and season with salt, sugar and lemon juice.

Now cut the goose into the portions and serve the red cabbage and dumplings and garnish with parsley.

Preparation time:

approx. 3 to 4 hours

-

Winter punch

Ingredients

1 l good red wine

500 ml strong white wine

100 g brown sugar

5 lemons

500 ml freshly brewed, strong black tea

Cinnamon

500 ml Arrack palm winePreparation

Mix the wines in a put and dissolve sugar in it. Squeeze 4 lemons and add the juice. Add the freshly brewed black tea, cinnamon and the Arrack. Finally put the pot on a hot hob and heat the punch until it nearly boils. Quickly take a sieve and using a ladle pour the punch into the glasses and decorate using a slice of lemon.